A spring will cease to flow if its source be dried up; a tree will wither if it roots be destroyed. In its main features the Declaration of Independence is a great spiritual document. It is a declaration not of material but of spiritual conceptions. Equality, liberty, popular sovereignty, the rights of man – these are not elements which we can see and touch. They are ideals. They have their source and their roots in the religious convictions. They belong to the unseen world. Unless the faith of the American people in these religious convictions is to endure, the principles of our Declaration will perish. We can not continue to enjoy the result if we neglect and abandon the cause.

—Calvin Coolidge, on July 5, 1926, in a speech commemorating the 150th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, and consequently the 150th birthday of the United States of America—

This article is part 2 of a 3-part series highlighting ten bedrock principles of liberty embedded in the Declaration of Independence.

Last time we reviewed the discussion, debate, and activity—parliamentary and otherwise—that led to the drafting and adoption of the Declaration of Independence to give birth to the United States of America. These watershed events took place in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania in the Second Continental Congress, during June and early July of 1776.

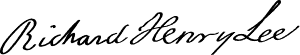

On June 7, Richard Henry Lee, a delegate from Virginia, presented a resolution to the Congress calling for the thirteen colonies to sever their ties to Great Britain. The first clause of the resolution read,

Resolved, That these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States, that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain is, and ought to be, totally dissolved.

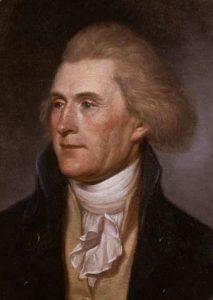

Although Lee’s resolution was not voted on until July 2, when the Congress voted to approve it, a Declaration of Independence already had been drafted and refined by a drafting committee—a group that became known as the Committee of Five—and by the members of the Congress themselves. Thomas Jefferson, who later would become the third President of the United States, was the Declaration’s principal author.

Bedrock Principles

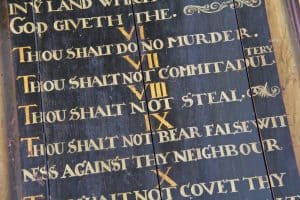

The Declaration of Independence affirms timeless principles that were revolutionary at the time and that remain revolutionary today. It is not difficult to draw connections between these ideals and biblical truths, for many “Declaration principles” are rooted in Scripture. In this article and the next, drawing from the words of the Declaration, we will examine ten ideals that are inherent in the document. They are not hidden, but in most cases they are assumed, and therefore evident by implication. Highlighting these tenets will demonstrate just how far America has departed from its foundation. Hopefully they also will serve as a warning to 21st-century Americans to rediscover these tenets, return to them, and embrace them once again.

As we have indicated, numerous edits were made to Jefferson’s draft by the committee and then by the members of the Second Continental Congress. Go here to read Jefferson’s original draft, and here to compare and contrast the original to the final version. You can listen to and download MP3 audio files of both versions at this page from the Monticello website.

We will not examine here the entire document but the most quoted and best known portion of it; and on our journey we will encounter numerous ideals on which the new nation was built.

Jefferson’s original draft reads,

When in the course of human events it becomes necessary for a people to advance from that subordination in which they have hitherto remained, & to assume among the powers of the earth the equal & independant station to which the laws of nature & of nature’s god entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the change.

We hold these truths to be sacred & undeniable; that all men are created equal & independant, that from that equal creation they derive rights inherent & inalienable, among which are the preservation of life, & liberty, & the pursuit of happiness; that to secure these ends, governments are instituted among men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed; that whenever any form of government shall become destructive of these ends, it is the right of the people to alter or to abolish it, & to institute new government, laying it’s foundation on such principles & organising it’s powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their safety & happiness.

The final version refines Jefferson’s draft in various places but does not alter his essential thrust or meaning.

When in the Course of human events it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another and to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation.

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness. — That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, — That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness.

In our discussion of these ideals, we’ll quote from both the draft and the final version of the Declaration. In those places where we do not specifically name which one we are quoting, we will be quoting the final copy.

Principle 1: God exists, has established an ordered and moral universe, and holds humanity accountable.

Jefferson’s draft affirms the efforts of a people “to assume among the powers of the earth the equal & independant station to which the laws of nature & of nature’s god entitle them,” and the final document upholds their efforts “to assume among the powers of the earth the separate and equal station to which the laws of nature and of nature’s God entitle them.” This assumes or presupposes that the people involved are not acting arbitrarily, but in accord with God and His revealed will.

Principle 2: Absolute truths exist and are knowable.

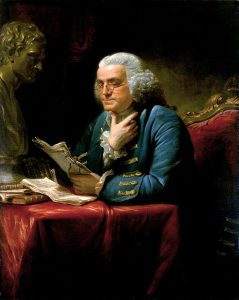

“We hold these truths to be sacred and undeniable,” Thomas Jefferson wrote. Honing in on and sharpening one aspect of the ideas these two adjectives highlighted together, the final document reads, “We hold these truths to be “self-evident.…” Most historians believe Benjamin Franklin initiated this change, but the question of who should be credited with it probably isn’t the most valuable nugget worth mining here.

Jefferson’s term sacred underscored God’s involvement in human affairs through divine bestowal of unalienable rights. This was an element the final version would explicitly emphasize only a few words later. His term undeniable highlighted the Founders’ perspective that the truths being upheld had to be acknowledged, but the reality of the day was that, in fact, “many people…did deny that mankind has unalienable rights. All the deniers would have to do to refute the claim is simply disagree; nothing more would be required.” By contrast, the term self-evident put the onus back on those inclined to claim unalienable rights were not real. A self-evident truth, by its very existence, rightly claims that those who deny it are foolish. Now, they may be deceived, and therefore worthy of sympathy and compassion—but sympathy and compassion are neither authentic nor helpful if those who supposedly are sympathetic avoid or water down the truth. The idea that a biological man actually can be a woman, or that a biological woman can legitimately identify as a man, is an example of a modern falsehood that must be countered with the truth. Compassion demands this. This and many other leftist ideologies demonstrate with utter clarity just how far Americans have drifted away from the beliefs the Founders upheld.

This is not to say that all self-evident truths are equally self-evident. Nor is it to say that all such truths are equally self-evident to all people. We’ve noted already that “many people” in the second half of the 18th century “did deny that mankind has unalienable rights.” The Founders’ recognition of self-evident truths—that alone—attests to their holding a biblical worldview. Alvin J. Schmidt writes that the term self-evident

has Christian roots going back to the theological writings of the eighth century. To the medievalists, “self-evident” knowledge, says Gary Amos, “was truth known intuitively, as direct revelation from God, without the need for proofs. The term presumed that man was created in the image of God, and presumed certain beliefs about man’s rationality which can be traced as far back as Augustine in the early fifth century.”1 Amos also shows that St. Paul in the Epistle to the Romans wrote that since the creation, even to the pagans, God’s “invisible attributes are clearly seen” (Romans 1:20 NKJV), that is, self-evident. In the previous verse, Paul says that these truths are phaneron estin en autois (evident by themselves). Thus, it is quite plausible that Paul’s biblical concept of “self-evident” knowingly or unknowingly influenced Jefferson [and the others] when he [—they—] declared, “We hold these Truths to be self-evident.”2

Even though not all the Founders were Christians, many were. Dr. D. James Kennedy indicates that the late Dr. M. E. Bradford of the University of Dallas, through his research, determined that fifty and perhaps fifty-two of the fifty-six signers of America’s founding document were “Trinitarian Christians.” That’s not all, either! Dr. Kennedy says as well that other experts “note that 29 of them had the equivalent of seminary degrees.” Try finding that many theologians in a group of politicians today! This was the case despite the fact that only one signer—John Witherspoon—was a pastor.

Regardless of how many of the 56 truly were believers, it is undeniable that on the whole they held to a biblical, or we could say a Christian, worldview. Consequently, they readily understood that certain rights are God-given, and therefore unalienable, inherent—and yes—absolute.

Principle 3: God and His laws establish the track on which men and nations must travel to attain happiness, fulfillment, greatness; and to reach their God-given potential.

While the Declaration of Independence frames this principle in the context of Colonial opposition to British tyranny and the forming of a new nation to secure and protect citizens’ inherent rights, the lesson has an even broader application. Both people and governments are accountable to God. Our Founders knew that men and women cannot live fulfilled lives by merely following their whims and desires, treading down whatever paths their raw appetites direct them. Rather, they must “assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God entitle them.” The word entitle is important here, and it appears both in Jefferson’s draft and in the final document. Entitle as the Founders used it is light years away from the meanings it and its various forms frequently carry today. How do we know this? Because according to the men who ratified the Declaration, that to which the people are entitled is granted and governed according to “the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God.” By contrast, today, people look to government for everything to which they believe they are “entitled.”

Entitle as the Founders used it is light years away from the meanings it and its various forms frequently carry today.

Take note! The parameters set by “the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God” are not nearly as restrictive as they are liberating. Within them, people can “alter or…abolish” government that refuses to secure and protect unalienable, God-given rights “and…institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness.” According to the Founders, this perspective of the people — the “form [that]…to them shall seem most likely to affect their Safety and Happiness” — also is governed and regulated by God and His laws. No wonder we find these lines in the patriotic hymn, “America, the Beautiful“:

America! America!

God mend thine every flaw,

Confirm thy soul in self-control,

Thy liberty in law!

Sadly, the idea that liberty and law go together is a foreign concept to Americans today. Many, if not most, see these two elements as totally contradictory. But they’re not! Not only are they compatible; they’re inseparable! How can a nation prosper? How can liberty thrive? Only under God!

- George Washington, in his Farewell Address that was printed and distributed widely in 1796, proclaimed, “Of all the dispositions and habits which lead to political prosperity, religion and morality are indispensable supports. In vain would that man claim the tribute of patriotism who should labor to subvert these great pillars of human happiness—these firmest props of the duties of men and citizens. The mere politician, equally with the pious man, ought to respect and to cherish them.”

- John Adams put it this way: “[I]t is religion and morality alone which can establish the principles upon which freedom can securely stand. The only foundation of a free constitution is pure virtue.”

- John Adams’s second cousin, Samuel Adams, said this: “[N]either the wisest constitution nor the wisest laws will secure the liberty and happiness of a people whose manners are universally corrupt.”

- Born a bit later than the Founders (on January 18, 1782), Daniel Webster became a powerful orator and lawyer, a member of the US House of Representatives, a US Senator, and Secretary of State under Presidents William Henry Harrison, John Tyler, and Millard Fillmore. Webster declared, “If we and our posterity reject religious instruction and authority, violate the rules of eternal justice, trifle with the injunctions of morality, and recklessly destroy the political Constitution which holds us together, no man can tell how sudden a catastrophe may overwhelm us, that shall bury all our glory in profound obscurity.”

If we and our posterity reject religious instruction and authority, violate the rules of eternal justice, trifle with the injunctions of morality, and recklessly destroy the political Constitution which holds us together, no man can tell how sudden a catastrophe may overwhelm us, that shall bury all our glory in profound obscurity.

—Daniel Webster—

By the way, the concept of “eternal justice” as Daniel Webster used it stands firmly against “social justice,” a movement that calls for government intervention to achieve “equality.”

Principle 4: God has created human beings equal in value, and He intends for them to be treated with dignity and respect.

Here we focus on the phrase, “all men are created equal.” Jefferson’s original words were these: “We hold these truths to be sacred & undeniable; that all men are created equal & independant, that from that equal creation they derive rights inherent & inalienable, among which are the preservation of life, & liberty, & the pursuit of happiness.…” After the gifted writer’s colleagues had made their revisions, the statement read, “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” Of course, the idea that all men are created equal is quite radical, and it was radical then as well.

Inevitably, someone will ask, Why did the Founders say this but not abolish slavery? It’s an important question. Yet to be fair we must

evaluate our Founders not in light of our own culture, but in light of theirs; America’s “Founders were born into a society that permitted slavery.”3 Despite this, some swam against the tide as they expressed resistance and even opposition to the practice.

Thomas Jefferson, himself a slaveowner, was one such man. In his original draft of the Declaration, he took the King of England to task for his role in the slave trade. He wrote,

he has waged cruel war against human nature itself, violating it’s most sacred rights of life & liberty in the persons of a distant people who never offended him, captivating & carrying them into slavery in another hemisphere, or to incur miserable death in their transportation thither. this piratical warfare, the opprobrium of infidel powers, is the warfare of the CHRISTIAN king of Great Britain. determined to keep open a market where MEN should be bought & sold, he has prostituted his negative for suppressing every legislative attempt to prohibit or to restrain this execrable commerce; and that this assemblage of horrors might want no fact of distinguished die, he is now exciting those very people to rise in arms among us, and to purchase that liberty of which he has deprived them, & murdering the people upon whom he also obtruded them; thus paying off former crimes committed against the liberties of one people, with crimes which he urges them to commit against the lives of another.

In this paragraph, Jefferson harshly condemned King George III; yet ironically, he also condemned the slaves by implication, at least with regard to certain actions (not, we should note, with regard to the color of their skin.) Still, we are foolish to ignore the strength of Jefferson’s case against slavery, one that was all the more remarkable because it was penned during an era when, and in a culture where, the practice was embedded in everyday life. We can scratch our heads in bewilderment over what to us appears to be Jefferson’s hypocrisy; but more realistically, doesn’t it appear that these are the actions of a man whose conscience has been stirred, but who knows he cannot overturn this aspect of the cultural landscape in a split second?

Moreover, Jefferson’s own involvement in the institution of slavery was deep, yet not fully because of his own conscious choices. Again, the Virginian was born at a time when slavery was the order of the day. Can we not understand he personally finds it difficult at one moment in time to do a complete about-face regarding the matter?

Do not misunderstand. I’m not defending slavery—not for a New York minute. I’m merely saying Jefferson’s action here represents a step in the right direction—for him and for a nation on the cusp of its birth. For articles that offer a more thorough discussion of the issue of slavery, racism, and the Founders, visit this page.

When the edits were made, the paragraph was struck, so the Declaration did not, and does not, condemn slavery explicitly. Yet it does so implicitly! Statements that remained in the document would prove in the decades ahead to be extremely powerful weapons against institutional slavery and other societal wrongs. While

the Founders did not immediately free the slaves, give votes to their wives, or invite the Indian tribes to sign the Declaration with them…all of the greatest advocates for human equality in America—Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and the Suffragettes, Martin Luther King Jr.—pointed to this passage in the Declaration to give force to their demands for justice.4

Thus, the concept that “all men are created equal” became one of the most powerful ever upheld by a nation. We can be grateful for this in many ways, but a word of warning is in order.

In recent decades, Americans foolishly have rallied around the banner of equality alone when, in the original statement on America’s “birth certificate,” the meaning of the word equal is informed, tempered, and shaped by the word created. Created, in turn, is linked inseparably to the divine title Creator. The implications of these realities, of course, are enormous.

In the Declaration of Independence, the meaning of the word equal is informed, tempered, and shaped by the word created. Created, in turn, is linked inseparably to the divine title Creator.

We must realize this and let it sink in! The equality among men that Jefferson, the Committee of Five, and the Second Continental Congress promoted and upheld is not one achieved through societal manipulation or government intervention, but one that already exists. It is an equality government has a duty to recognize and protect, a God-given attribute in which unalienable rights are deeply rooted and in which they find their sustenance. We have ignored this point to our own peril, and we must rediscover it and appreciate it once again.

More to Come

At this point, we’ve highlighted and discussed four out of ten “bedrock principles of liberty” that are enshrined in the Declaration of Independence. Our list of ten is by no means exhaustive, but I hope it will be transformative in the sense that, if we who love and appreciate authentic liberty can reclaim these truths, we’ll be far better able to point people to a fresh hope for the preservation of liberty, freedom, and prosperity in our land. Be keenly aware that the prosperity of which I speak isn’t a greedy prosperity, but one that benefits America as a country, all Americans as individuals, and the world.

We’re not quite halfway through our list. On Wednesday, July 10, I’ll release part 3, the final installment in this series.

Be sure to return!

Part 3 is available here.

Copyright © 2019 by B. Nathaniel Sullivan. All rights reserved.

top image credit: Liberty Bell Postage Stamp, 1926 — to learn more about the Liberty Bell, go here.

image credit: photo of a portrait of Richard Henry Lee hanging at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, DC

image credit: Monticello

Notes:

1Gary Amos, Defending the Declaration: How the Bible and Christianity Influenced the Writing of the Declaration of Independence, (Brentwood, TN: Wolgemuth and Hyatt, 1989), 78. [This is the source information cited by Alvin J. Schmit.]

2Alvin J. Schmidt, How Christianity Changed the World, (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2004), 254-255.

3William J. Bennett, America, the Last Best Hope—Volume 1: From the Age of Discovery to a World at War, 1492-1914, (Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 2006), 122.

4Bennett, 86.

Be First to Comment